By Alexa Ard

At 14 years old, D.J. Fenner, now a freshman on the Nevada men’s basketball team, allowed his entire being and purpose to be consumed by basketball. The decisions he made were based off of what he could get out of the sport that was his escape, and in his eyes, the definition of D.J. Fenner.

He believed that in order to make it to the NBA, his values, time and energy all had to be invested in basketball. “I thought if I wanted to play in the NBA, then I have to simply define myself as a basketball player,” said Fenner, a six-foot-six guard.

“I felt like in order for me to be the best at basketball, then I literally have to forget about everything else except basketball.” In addition, he was faced with stereotypes throughout his life because of what people see when they look at Fenner a tall, athletically built black male even though he’s just as much Filipino as he is black. Still to this day, people who don’t know his name approach him and say without a stutter or pause, ‘You’re a basketball player.’

It was no longer just Fenner’s view of himself, but that of others who didn’t personally know him as well. After a summer league game following his freshman year of high school, the idea of being more than just a basketball player was brought to his attention.

He had arrived late, so, Michael Kelly, head coach of the Seattle Prep varsity basketball team, didn’t let him play. Following the game, Fenner approached Kelly and told him he might need to go to another school because he wasn’t sure that he was “fitting in” at Seattle Prep.

“He was basically saying ‘Because I’m being held accountable I think I need to go to another school,’ and what I responded with was, ‘You’re spending too much defining yourself as a basketball player,’” Kelly said. “You’re making decisions just solely based on basketball.” Fenner’s response to his advice: laughter. The shooting guard now admits that at the time he was a cocky high school freshman who didn’t want to believe he was any thing other than a basketball player. “I felt like that’s what I was here for just to play basketball,” Fenner said.

Five years after this incident, he was no longer the Seattle Prep freshman who thought he knew it all. Each day of his last semester of high school, Fenner could be found spending hours working on Final Cut Pro to make a 20 minute documentary called “Beyond the Court.” He directed, edited and starred in this short film with the help of Andre Varnado and Demetrius Simmons, his friends and classmates in the video production class.

The themes of the film range from the escape Fenner found in nature and on the basketball court, to family and a father, a former NFL player, who he wishes would have been more present in his life. One of the main ideas of the film is stereotyping. What viewers don’t get to see from the film is that he also plays piano and guitar, which he taught himself how to play to serve as his other outlets. Also, although he likes rap music, he enjoys punk rock as well. He said these are a few things that people are sometimes surprised by because they’re used to just seeing him on the basketball court.

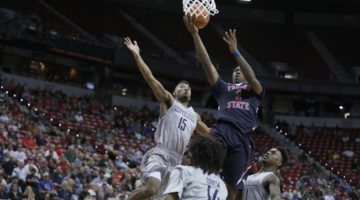

Nikolai Kolupaev /Nevada Sagebrush D.J. Fenner admits that there’s a lot more to college level play than high school such as the importance of help defense and the various schemes.

Leaders

There is even a portion of the film where students at the predominantly white school are asked, “Who is D.J. Fenner?” The answers include: “he’s a basketball player,” “he’s on the basketball team,” and “he balls so hard.” “He doesn’t need to fall into those kinds of stereotypes,” Kelly said. “He doesn’t need to be defined by what other people think he should or shouldn’t be.”

Kelly explained that once Fenner navigated away from the tunnel vision of being the best basketball player that everyone notices, he was then able to truly experience life. And ironically, that’s when he became one of the top players in Washington and last year’s The Seattle Times Player of the Year averaging 27.3 points as a senior. He shined on the court, but he had begun to use the sport as a tool to help others improve their game as well.

“Coach Kelly kind of took D.J. under his wing and tried to teach D.J. things that a man, a basketball player, a student and a son should know to become the young man that he’s become today,” said Carolyn Fenner, Fenner’s mother. Fenner said he hopes that one day, people can just be seen as people without stereotyping based on appearance or solely defining themselves based on one factor.

He hopes to play a role in that change, which was what he tried to portray through “Beyond the Court.” “There’s some basketball players out there who truly believe that’s all they are, they’re nothing more than that,” Fenner said. “It doesn’t necessarily upset me, but it makes me kind of sad because everyone’s more than just one thing.”

However, Fenner has continued to experience and see stereotyping during his time in college. He hopes to be a part of the change, but admits it will be a difficult obstacle to overcome. One example from his time in college thus far was when a girl didn’t want to hang out with him and a couple other girls at the same time because she didn’t want to look like a “groupie.”

This is one of the stereotypes he said he’s heard most. “You play basketball, so then you must have a lot of groupies,” Fenner said. “Some basketball players might, but not all of them.” He’s also found additional outlets since he’s started college, one being homework. “This might be a weird one, but I actually enjoy doing homework,” Fenner said with a laugh. “Because I play basketball so much that sometimes it’s nice to forget about homework so when I actually sit down and do the homework I can focus on it.” He enjoys doing homework for business calculus and sociology the most.

He admitted that sometimes math can be stressful, but once he masters the formula it boosts his confidence he compared it to playing a game. He has seen the most playing time of the three freshmen on the team averaging 15 minutes per game. Yet, he’s determined to make more of an impact in the game he loves.

He sees himself being more of a force for Nevada in the future. “I think next year will be way different because I know what I have to do in the offseason in order to get to where I want to get,” Fenner said.

Alexa Ard can be reached at aard@sagebrush.unr.edu.