Photo: (CC) Somos El Medio/ Flickr.com

People march in Mexico City on Monday, Dec. 1 and demand that the missing students be returned unharmed. The poster on the bottom right reads, “I am tired of the murderous government.”

By Rocio Hernandez

On Sept. 26, a group of more than 40 Mexican students were on their way to Iguala, Guerrero to protest the speech of Maria de los Angeles Pineda, the wife of Iguala’s mayor.

Local police stopped the students while they were inside buses and opened fire.

Vice News created a documentary that featured a video recorded by a student who was present during the incident. In the video, a student can be heard asking officers why they were shooting at him and his peers. The student claimed that the group was unarmed.

Six individuals, three of them students, were killed during the incident. Some students were able to flee from the scene. However, Mexican authorities reported that 43 others were kidnapped by police officers.

Deborah Boehm, an associate professor at the University of Nevada, Reno, was in Mexico City when she first heard that 43 students had been abducted. She has done research on Mexico and topics such as transnationalism and globalization. Boehm noted that political violence has taken place in Mexico for some time.

“There have been different periods of time in history when the [Mexican] state has used force against its own citizens and I think what is especially unsettling about the students is that it was the government who was responsible for it,” Boehm said. “That’s a form of violence that is especially hard to think about and there is no way to make sense of it.”

After a series of arrests and investigations, Mexico’s Attorney General Jesus Murillo Karam told CNN that he suspects that the students were handed over by Iguala’s mayor, Jose Luis Abarca, to a Guerraran gang called Los Guerreros Unidos who then killed and burned their bodies beyond recognition.

On Saturday, Dec. 6, the Associated Press reported that one of the missing students’ remains was identified. The Argentine forensic team in charge of the investigation confirmed that bone fragments found by investigators contained traces of the DNA of 19-year-old Alexander Mora Venancio.

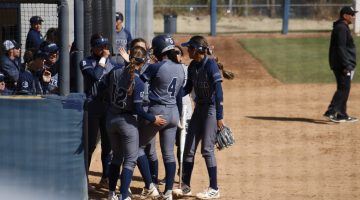

This issue has reached beyond Guerrero to the University of Nevada, Reno campus. When UNR’s Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán’s organization co-President Natali Castro read about the students, she felt devastated. She considered the abduction of the students an injustice and urged her organization to do its part and raise awareness of the issue.

The names and faces of the Mexican students are displayed on a banner hanging from a staircase inside of the Joe Crowley Student Union as a tribute to their disappearance. The banner is one of the first things that the organization has done to support the cause. Castro wants UNR students to take the time to read it and sympathize with their international peers.

“I just feel so privileged that I can go and protest and not be afraid that someone is going to take me or something bad is going to happen to me because it’s allowed here,” Castro said. “These [people] are our age and just to see that they were fighting for their rights and this ended up happening to them, no one deserves that.”

Most students that were kidnapped were from the Escuela Normal Rural de Ayotzinapa, a Mexican college, studying to become future educators in areas affected by poverty.

“[The 43 students] symbolize the hope for the nation and when people talk about needing to develop in Mexico, for example economically, that’s exactly what these young people were planning to do, to give back to their nation. And the idea that people in that situation would be [subjected] to violence such as this, I think, is especially unsettling,” Boehm said.

Along with the banner, UNR’s MEChA will be hosting a forum for students and community members to help them comprehend what is happening in Mexico.

“I applaud their efforts to help students understand their connection to global issue and I think that as an institution that’s something that we can contribute collectively to sort of think through these difficult issues, issues of social justice around the world, to think about ways that we at a local level can also help bring about change,” Boehm said.

Kimberly A. Nolan García, a professor at Mexican public university Centro de Investigación y Docencia Economícas, often accompanies her students to marches. She said that she has noticed that more people have attended the protests, even those from groups that don’t normally take place in political demonstrations such as wealth families. She has also seen that the issue has picked up attention from American universities such as University of California, San Diego.

While these added factors make Nolan García hopeful that a positive change can occur, she still urges students to get involved in any way that they can. Nolan García said that if students were to write letters to President Obama, hold events or tell their community about what’s going on in Mexico, it could have a significant impact on the country.

“[The Mexican government will] listen to the international community,” Nolan García said. “They can’t afford not to.”

Boehm said that one of the things she would like students to gain from college is to see their place in world and in the bigger picture.

“Engaging with a topic such as this is an opportunity to think through of the struggles of the current moment and what kind of solutions are out there for all of us to bring out change,” Boehm said.

In Mexico, protesters continue to demand justice from the Mexican government, as well as the safe return of the remaining 42 students.

“People are standing up,” Castro said. “Finally they are not afraid anymore.” Castro said. “Those students gave them hope.”

Rocio Hernandez can be reached at rhernandez@sagebrush.unr.edu and on Twitter @rociohdz09.