Thursday night, someone tagged several swastikas inside Church Fine Arts’ graffiti stairwell. Above the largest read the slogan, “[is] this political enough for you?”

What we know ends there. As of print time, we, as a campus community, have yet to discover who did this or why. And those are two very important questions, because this can easily be one of two scenarios.

First, the most common hypothesis, that this was the work of a white supremacist or a white nationalist or, at the very least, a racist. With what happened in Charlottesville over the summer (and the appearance of the University of Nevada, Reno’s very own Peter Cvjetanovic at those events), it’s not a stretch to think that there are white supremacists and white nationalists on this campus.

However, there is an alternative option: that this was the work of someone who isn’t ideologically white supremacist, merely someone using the symbol for the attention they know it will get. It may be unlikely, but it’s certainly not impossible considering how charged and how tense the political climate is these days. To use the swastika—especially on this campus—is to guarantee someone, if not everyone, takes notice of your message.

In either case, we need to talk about white nationalism as it relates to this campus, because there’s clearly something there. Charlottesville and these swastikas can’t be—or at least very likely aren’t—a coincidence. And even if they are, to see a symbol like the swastika appear here is to beg the question:

What are we doing wrong?

For starters, we acknowledge that it’s hard to say. Pinpointing something like this isn’t easy, especially considering the sheer number of students who go to this campus who may or may not believe in something like white nationalism, white supremacy or just racism more generally.

But maybe a first step might be making sure these ideas are challenged in the classroom before they start worming their way into the wider world. This is a college campus, and as such, we should take whatever opportunity we have not just to prove that these ideas are wrong, but also why these ideas are wrong.

It’s a crucial rhetorical step that’s often left untaken, and it means that those who hold these racist dogmas usually leave the classroom undaunted, and therefore unchallenged.

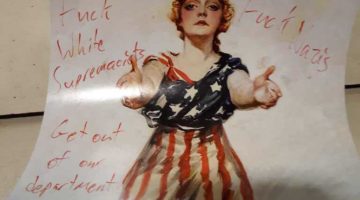

Moreover, for much the same reason, we can’t use anger alone to fight the ideologies that undergird white nationalism. We’ve said it in the past, but it still holds true today: saying f— Nazis won’t change the mind of someone who already thinks like a Nazi. Sure, it may be cathartic, but functionally speaking it drives those who already harbor these ideas further away from the mainstream and toward the twisted community that instilled those ideals in the first place.

We’ve also got to make sure that we’re holding ourselves to the same standard, too, and that means being able to explain why diversity and multiculturalism are good things for society. If we can’t do that, then it’s too easy for those ideologically opposed to such ideals to dismiss them outright and never give it another thought.

But no matter what, we’ve got to do better.