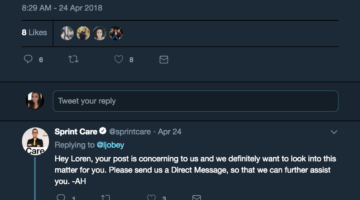

Screenshot of www.wearyellowforseth.com

Above is a screenshot of the Wear Yellow for Seth website designed to aggregate social media support photos.

In the 21st century, slacktivism seems to be the norm. As defined by Oxford Dictionaries, slacktivism is “actions performed via the Internet in support of a political or social cause but regarded as requiring little time or involvement, e.g., signing an online petition or joining a campaign group on a social media website.” With the expanding role of social media in the lives of millennials, more and more people pat themselves on the back simply for contributing to a cause’s conversation without actually enacting any change. The following three examples have been some of the most popular in recent history.

WEAR YELLOW FOR SETH

Snapchat blew up in the UK and major US cities last weekend as people were flocking to wear yellow for a boy named Seth that had been born without an immune system. His parents made an impassioned plea to social media users to wear yellow, the boy’s favorite color, in hopes of increasing his chances of receiving a bone marrow transplant. In short snap videos, people showed off their yellow shirts, mugs and even electric drills to show that they supported the boy’s survival.

While it’s a nice thought to show support for the boy, many people went about their days feeling they had done a good thing when, in reality, their yellow shirt would mean nothing in helping those who actually need bone marrow transplants. There are a variety of organizations that accept bone marrow donations to be given to those suffering with rare diseases. It can be a long process to donate, as the organization must find good matches between donors and receivers, but it means far more in saving Seth’s life than singing Coldplay’s “Yellow” so that Snapchat users can applaud your kindness.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m sure Seth’s parents were overwhelmed by the support by those wearing yellow, but many people need to remember that they haven’t necessarily done anything other than showing support. What most people have ignored is that they could text a telephone number to raise money for Seth. Wearing yellow just doesn’t go far enough — raising attention doesn’t accomplish anything unless people follow through on the call-to-action.

ALS ICE BUCKET CHALLENGE

From Justin Bieber to David Beckham, the Internet was swept by the phenomenon of people throwing buckets full of ice water on their heads in order to raise awareness and donations for Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, also referred to as “ALS” or Lou Gehrig’s disease. While it was one of the most prominent examples of social media creating a strong philanthropic movement, it was also one of the clearest forms of slacktivism that our society has seen in the 21st century.

It should be noted that the movement did create awareness of the disease. Before the popularity of “the Ice Bucket Challenge,” the ALS Wikipedia page had been visited by 1,662,842 people in one full year; with that said, an article from the BBC noted that, “from 1 August to 27 August this year, the ALS Wikipedia page had 2,717,754 views.” However, while the videos increased attention and donations for ALS, many people failed to actually do their part in making a difference.

Time and time again, friends would create their own Ice Bucket Challenge videos to join in on the excitement that the world was experiencing. When I would ask those same friends if they donated to an ALS-focused charity, they would often tell me that they did their job simply by sharing their own video. By buying the ice and making a video, people felt that they had done their jobs in fighting the good fight.

What many people seemed to forget was that the caveat to not participating was donating $100. The movement took off because people were avoiding the process of actually donating money. Granted, the challenge did boost donations, but it seems that a significant number of people chose to make a video in lieu of donating. They were able to sleep easily that night believing they had helped fight ALS, when in reality, they had only accepted the challenge in an attempt to avoid actualizing real change for the movement.

KONY 2012

Perhaps the first major form of slacktivism that many people experienced was the famous Kony 2012 video that was produced by nonprofit organization Invisible Children, Inc. The video was meant to start a movement to call for the imprisonment of African cult and militia leader Joseph Kony. The video painted a picture of the horrific acts Kony and the Lord’s Resistance Army had orchestrated in various regions throughout Africa.

The success and virality of the video was evident, but many failed to actually delve deeper into the truth of the situation itself or the nature of Invisible Children Inc. as a nonprofit entity. The popular video oversimplified the truth of the situation, portraying it as black and white and ignoring the various shades of gray in African history. Instead of conducting their own research, hundreds of thousands of people (particularly young people) donated to the cause without taking the time to understand where or how their money might be spent.

Invisible Children, Inc. advocated for foreign intervention, which certain African communities feared would only exacerbate the situation. While some may still have donated their money upon understanding the truth, the problem with the video is that the call-to-action was to donate as opposed to educating oneself. Instead of researching the historical context and potential solutions, people chose to rely on an organization they knew nothing about to take the best action — an action that many scholars have disputed over time.

Slacktivism is a dangerous concept because it truly takes away from understanding an issue at its core. While it has had some successes in raising money or awareness of certain causes, it does little in making change a reality. It’s time our society focuses on finding real solutions as opposed to simply relying on the pushing “share” on Facebook.

Daniel Coffey studies journalism. He can be reached at dcoffey@sagebrush.unr.edu and on Twitter @TheSagebrush.